For over seven decades, Pakistan has announced industrial revival plans with striking regularity—and watched them falter with equal consistency. From the import-substitution strategies of the 1950s to the “Make in Pakistan” rhetoric of recent years, the country’s industrial policy has remained trapped in a cycle of ambition without execution. While regional peers like Bangladesh, Vietnam, and India have leveraged industrial policy as a tool for export growth and job creation, Pakistan’s manufacturing sector continues to stagnate, contributing less to GDP and exports than its potential allows.

The problem is not a lack of intent. It is a chronic failure to translate policy promises into institutionalized, sustained, and politically insulated action.

A History of Short-Termism

Pakistan’s industrial policy has historically been reactive rather than strategic. Governments announce incentives—tax holidays, concessional financing, tariff protection—without embedding them into a long-term framework. Each political transition disrupts continuity, resets priorities, and introduces new schemes that rarely outlive the administration that conceived them.

This short-termism discourages serious industrial investment. Manufacturing, particularly in value-added sectors, requires predictability in taxation, energy pricing, and trade policy. Pakistan, however, has frequently altered tariffs, export incentives, and regulatory regimes midstream, creating uncertainty that investors—both domestic and foreign—are unwilling to absorb.

Protection Without Performance

One of the most damaging features of Pakistan’s industrial policy has been its reliance on protectionism without accountability. Industries have long enjoyed high tariff walls and regulatory shields, but with few performance benchmarks attached. Unlike East Asian models, where protection was conditional on export targets, productivity gains, and technological upgrading, Pakistani firms were rarely compelled to compete globally.

The result is a manufacturing sector that remains inward-looking, inefficient, and heavily dependent on state support. Protected industries passed costs onto consumers, failed to innovate, and resisted reforms—turning industrial policy into a tool for rent-seeking rather than competitiveness.

Energy, Infrastructure, and Cost Disadvantages

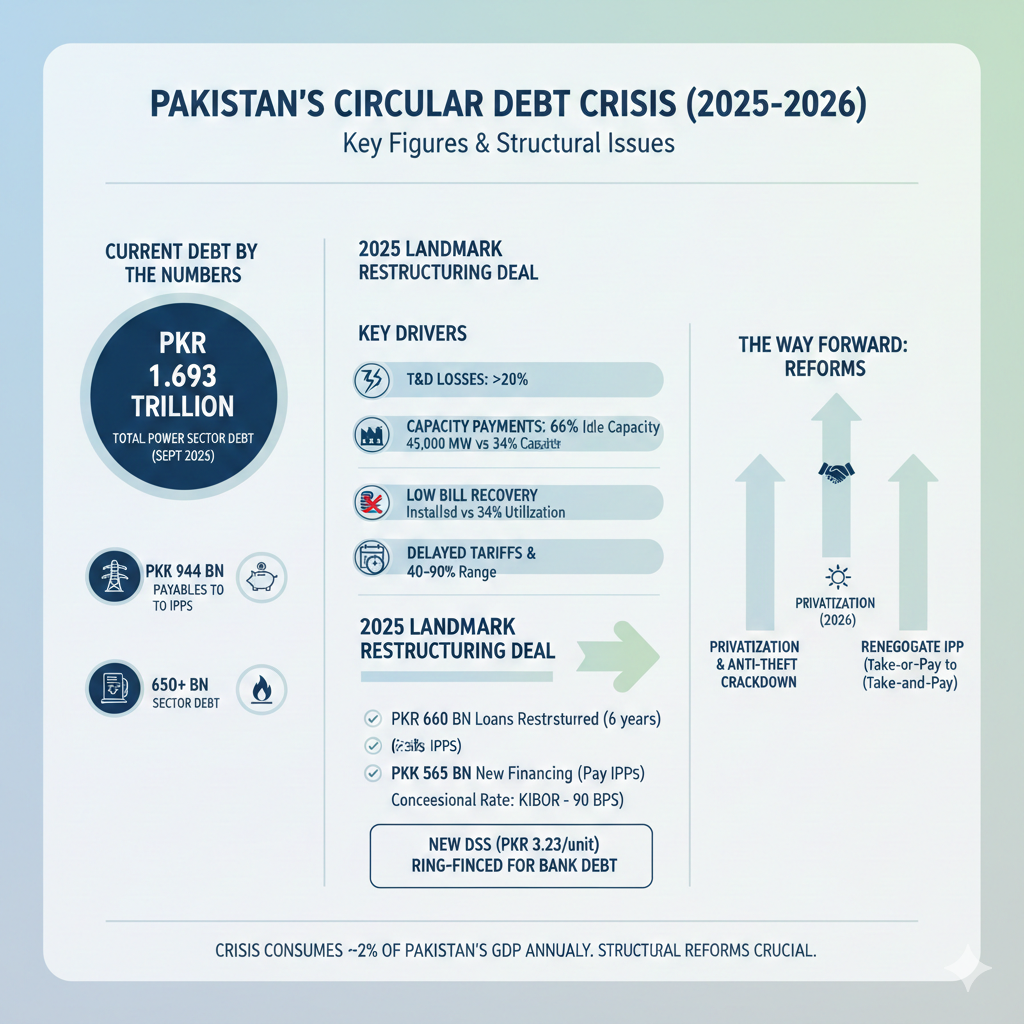

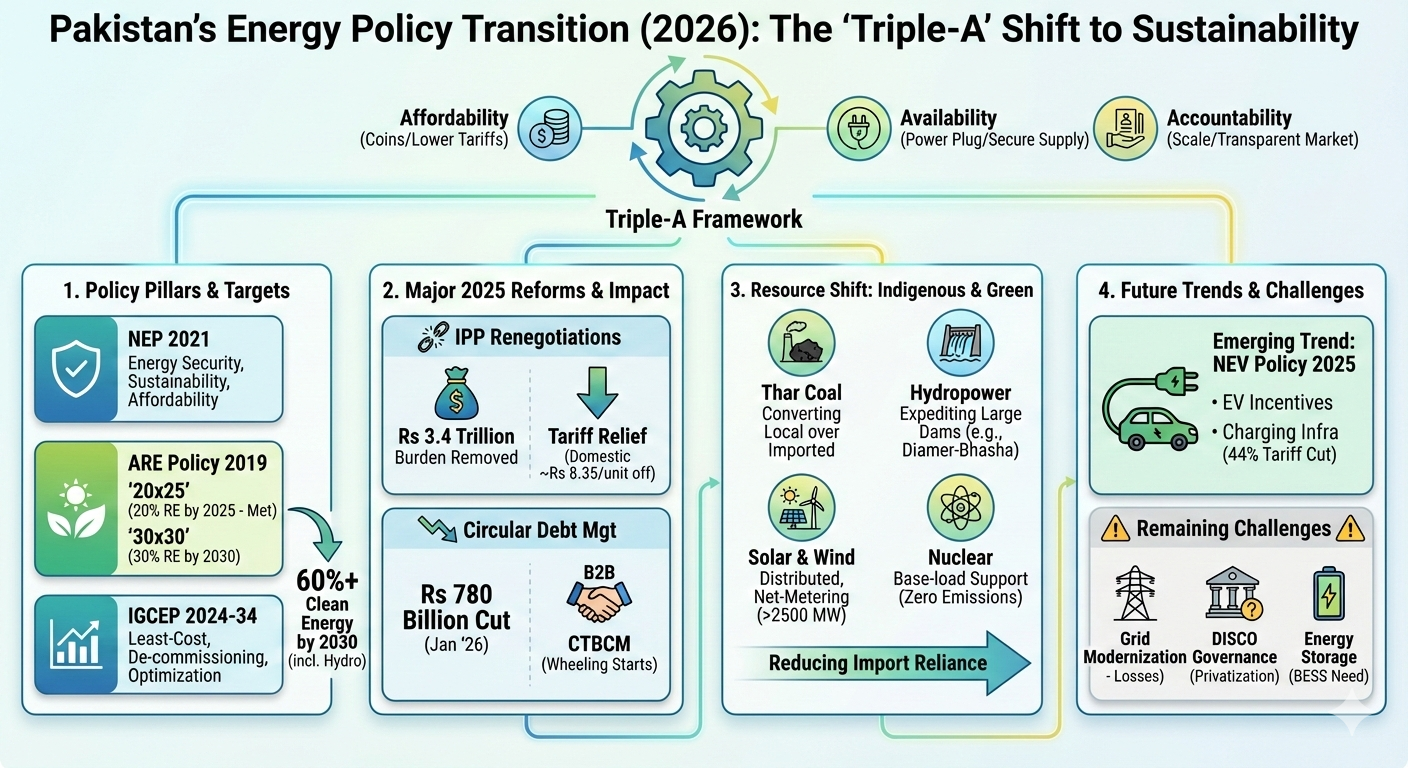

Industrial competitiveness is fundamentally shaped by factor costs, and Pakistan fares poorly on this front. Erratic energy supply, among the highest electricity tariffs in the region, outdated logistics infrastructure and weak transport connectivity have collectively eroded industrial productivity.

While successive governments have acknowledged these constraints, policy responses have been fragmented. Energy subsidies, for example, have been applied inconsistently—benefiting select sectors temporarily without addressing structural inefficiencies in generation, transmission, and governance. As a result, manufacturers face volatile input costs that undermine export pricing and long-term planning.

Export Myopia and Sectoral Concentration

Pakistan’s industrial policy has failed to diversify exports beyond a narrow base dominated by low-value textiles. Despite repeated announcements of export-led growth strategies, little has been done to support sectors such as engineering goods, electronics, chemicals, or value-added agro-processing.

In contrast, Bangladesh strategically aligned its industrial policy with global value chains in garments, while Vietnam integrated manufacturing into regional supply networks through trade agreements and regulatory reforms. Pakistan, meanwhile, treated exports as an outcome rather than a policy objective—assuming they would follow automatically from incentives rather than targeted capability development.

Institutional Weakness and Policy Fragmentation

Perhaps the most critical weakness lies in institutional capacity. Industrial policy in Pakistan is scattered across ministries, provinces, and regulatory bodies, with limited coordination or accountability. No empowered central institution exists to design, monitor, and adjust industrial policy based on measurable outcomes.

Moreover, devolution after the 18th Amendment further complicated industrial governance without establishing effective coordination mechanisms between the federation and provinces. The result is policy overlap, regulatory confusion, and diluted responsibility.

The Way Forward: From Rhetoric to Results

If Pakistan is to escape its cycle of industrial underperformance, it must fundamentally rethink how industrial policy is designed and implemented. This requires shifting from ad-hoc incentives to a rules-based framework anchored in competitiveness, exports, and productivity.

Key reforms must include conditional support tied to performance, stable trade and tax regimes, energy pricing reforms that reward efficiency, and a deliberate push toward export diversification. Most importantly, industrial policy must be institutionalized beyond political cycles—owned by capable technocratic bodies and shielded from short-term political interference.

Industrialization is not a slogan; it is a sustained policy choice. Until Pakistan treats it as such, its factories will continue to underperform, its exports will remain limited, and its economic growth will remain vulnerable.

- 6 in 1 jar and bottle opener–Eight sizes of circular openings make the jar opener extremely convenient to open small an…

- EFFECTIVE AND EASY TO USE :The long handle provides sufficient leverage, rubber lining helps provide a firm grip on the …

- APPLICATION TIP:Both sides of the opener can be used to accommodate different sizes of lids, choose a suitable opening t…